Once every few years a group of Tsavo eles journeys to Amboseli. Recently, we did the same. We flew into the late afternoon sun, away from the ochre dusts, towards Kilimanjaro. Ever since I was a child in Cornwall, I have loved traveling west – it’s always felt like going home, with the added gift of another minute or two of light at the end of the day.

This was no different – we flew past the cliffs of Kichwa Tembo, tracking the Tsavo river. We passed over an old friend of a fig tree we had filmed for ‘The Queen of Trees’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xy86ak2fQJM). We were well above bird watching height, but I knew the shapes streaming from its canopy would be green pigeons – just as I knew their presence meant the tree must be fruiting.

Then on to Mzima – in the late light, the water looked dark and mysterious – it still held secrets, but there was not a hippo in sight. Before the last drought, there had been sixty. They’d been our noisy neighbours for almost five years – now they are gone, and the ecosystem their dung supported, has largely collapsed. When we’d last been there, we’d found that the hippos were starving – but because they weren’t dying in the water, the first deaths went unnoticed. Emergency supplemental feeding, a ‘care package’ of alfalfa and hay, prooved too little, too late. Today, Mzima is a silent spring.

When we lived there, I’d have laughed at the suggestion that, within a decade, the film we’d made would become an historical document. Even now, I find it hard to believe.

We flew on, chasing the light, with the green-soft curves of the Chyulu Hills on one side and the foothills of Kilimanjaro on the other. It felt as if we’d entered a broad valley – at its apex was Amboseli. We could see it from thirty miles away – the wind whipping up the dust on the dry lake bed made it look like the land was on fire.

Even from the air, Amboseli’s elephants felt different to Tsavo’s. As we came in to land, families, heading for higher ground for the night, didn’t glance up or change pace – they walked in calm, orderly lines. On the ground, the difference was more marked. The elephants didn’t move from beside the track, as we passed. Throughout their lives, they’ve been habituated to researchers and tourists – they have personal histories and names. There is so little poaching, that inside the park they know they are safe, and respond by being approachable and trusting.

Having been around Tsavo’s feisty elephants for the last few years, a trip to Amboseli felt like visiting a finishing school. The elephants are genteel, the pace relaxed, movements considered and minimal. If caught by surprise, rather than charge, they will step out of your way – almost apologetically.

My first impression was that the elephants looked ‘clean’, but it took me until the next day to realize why. It wasn’t the washed ‘clean’ that hours in the swamp produces, it was that their flanks had no wounds. In Tsavo, many elephants have abscesses as a result of poisoned arrows. In Amboseli, I’ve not seen one.

Despite it being the end of the dry season, the elephants looked well, the babies playful and plump. The last time I’d been there was at the height of the 2009 drought – the worst since 1961. The elephants were emaciated, dull-eyed and listless – their trunks dragged in the dust. That year, almost all the babies had died.

Ironically, there was no shortage of water as the park’s famous springs never stopped flowing. Instead, Amboseli’s herbivores were dying of starvation. That September, I’d filmed the death of an elephant calf for the BBC. I had expected the rains to break shortly afterwards, but they never did. Within a few weeks, what had been a crisis developed into a catastrophe.

We decided to go back. I was shocked at the change. Animals were dying in their thousands. The stench pervaded the park. It was impossible to escape it, or wash it from my clothes. Skeletal wildebeest and zebra now stood foursquare and shaking – their withered muscles spasming – for if they ever lay down, they’d be unlikely to stand again. The full horror wasn’t apparent until, one evening shortly after arrival, I climbed onto the land-rover roof and counted over 500 carcasses within a mile.

In the days that followed, I saw life leave the eyes of zebra and wildebeest. But amidst all the death, I never once saw an animal fall, which made me wonder about those final moments.

Early one morning, I found a particularly emaciated wildebeest. I decided to stay with it. I thought I should film it collapse – it would be a moment, I felt, that encapsulated the three years of failed rains, and the terrible consequences for the grazers.

I thought it would be easy.

I followed the wildebeest at a distance for I didn’t want my presence to tip the balance against it. After an hour I was amazed that it was still upright. It walked in a daze, as if it had retreated somewhere deep inside itself. Its hips were sharp and angular, its head looked disproportionately large, its eyelashes caked with fine dust. It occasionally stopped, head hanging, legs wobbling. It seemed to sleep, standing up. As it shook more, I’d start filming, but it never fell. Sometimes it would open its eyes wide, as if surprised at where it found itself.

At others, it would lurch forward as if going down, but the momentum would somehow get turned into a step, and then another…and it would start walking again. I followed it for hours. It never let up. By midday, I was hot and frustrated that it was taking so long. I’d planned to look for elephants. My time in the park was limited and I was questioning the wisdom of my decision. I considered changing subjects, but I thought the wildebeest was close to death and by now, it paid no attention to the vehicle, so I decided to stay with it.

As the day wore on though my feelings started to change. I still wanted to film its collapse, but I started to admire its tenacity. I still wanted it to end quickly, but now, it was as much for the wildebeest’s sake, as for mine.

There was no single point that the situation reversed, but ever so gradually, over the course of the afternoon I came to realize that what I wished for had changed. I no longer cared whether I’d film it, I just wanted that individual to survive. I’d followed it for almost twelve hours. I was hot and thirsty, and tired. It was nothing compared to how the wildebeest must have felt. Now, when it staggered and kept going, I gave a silent cheer. As the light faded, and it lurched off into the darkness and dust – I just hoped it would survive.

I learnt from that day – that instead of trying to impose my will, I should have observed and listened. More importantly, I learnt about determination and hope. I drove back to camp in awe of that wildebeest, and the power of its life-force – of its determination to stagger on, in the hope of finding a small patch of grass, that might sustain it a few more hours, another day…

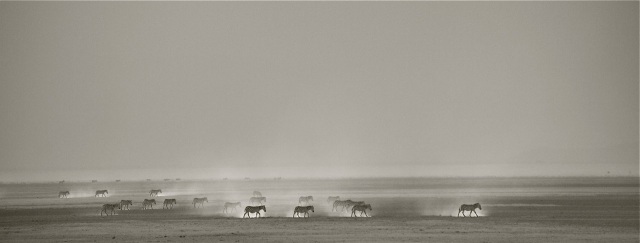

Today, in Amboseli, there are thousands of wildebeest and the population is recovering. I like to think the individual I followed five years ago, might be among them. They all look dusty-sleek, and there are hundreds of calves. They have the energy to canter, and head-twist their way across the plains.

Two years after the drought, there was an elephant baby-boom. The boomers are now mischievous, tail-pulling toddlers – shadowing their mothers on the daily trek to the swamp. Grass grows through old zebra skulls, and the herds walk past them as they file in to drink. There is little to remind us of how desperate it was – only five years ago.

Yesterday evening, as we flew back to Tsavo, I looked down on Mzima and saw a lone hippo leaving the water. It will take a long time for Mzima to recover. It might be decades before it returns to its full glory – as a fish-filled, hippo-aquarium.

I was encouraged by what I’d seen in Amboseli, for it reminded me that ecosystems have a huge capacity to heal and recover.

It will take time – but it gave me hope.

© Mark Deeble & Victoria Stone and A Wildlife Filmmaker in Africa, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mark Deeble and A Wildlife Filmmaker in Africa with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Moved to tears, sad to read hippo no longer dance in Mzima Springs, but looking forward to seeing the Baby Boomers in Amboseli myself in December. I’d like to think that old gnu made it, too. Most evocative writing and images.

Moved to tears too. Glad I am not alone.

Without hope we would all give up. I really enjoyed reading this piece and hope he did live to run with the herd again.

Reblogged this on It Is What It Is and commented:

Hoping for full recovery …. love the story & writing. Peace …

Beautiful and poignant. Thank you for sharing.

Beautifully written – and very moving. Though I have traveled very little, I had similar observations of elephants in the Maasai Mara last year. I expected to find many identifying characteristics – ear notches and tears, scars, broken &/or uneven tusks, etc. Instead I saw many elephants with totally intact ears, symmetrical tusks, and just beautifully “whole” . They also were very calm, and even curious, though sadly there now has been more poaching within that ecosystem

I must pass on your hippo observations to Karen Paolillo at Turgwe Trust, who kept alive the last 13 hippos left in the Turgwe River, and has bravely defended a “hippo haven” there. in Zimbabwe – at times life-threatening for her and her husband, during the political unrest and land invasions.

Thank you for opening my eyes further to see how much “life wants to live”

Yes ecosystems recover. Thank goodness. Look at the miracle of Chernobyl for one amazing example. Sometimes we humans just need to get out of the way for the recovery to happen. I have heard Cynthia Moss describe the effects of the drought on her well researched Amboseli elephants and happy they recovered. We conservationists need hopeful words. Thanks. Lori from SavingWIld.com

Thank you. Poignant reading

What a wonderful story, the will to go on and survive in all creatures including the human race is awe inspiring.

A beautifully written article, thank you. I have not visited Africa but the places and the animals must be a wonderful experience. It all sounds beautiful.

Thank you for this moving post. The haunting photo of the wildebeest really moved me. I love your posts and photographs.

Patti

A moving post.

You write so beautifully if words could save wildlife, these would. Thank you.

as ever, beautifully written… thanks Mark

What a gift. Thank you, Mark (and Vicky). xx

So good to have your eyes on all this….if such things are left unsaid it is as if it never happened. That silence would be an even larger tragedy.

Thank you so much that was one of the most beautiful pieces of writing i have read in long time, it moved me to tears i found myself cheering on the wildebeest again thank you for your words from the heart….

Reblogged this on Hannah Strand.

I read this several times and each time I thought I was right there with you, seeing and feeling exactly what you were feeling. I was sure that it was partly because of your vibes that the poor wildebeest kept going …

Brilliant writing, Mark, to match your amazing photos. V interesting to hear your impressions of Amboseli, and of the drought and recovery. And so very refreshing to see the message that ecosystems are resilient, if they are allowed to take their own course. I recall how the ill-advised attempt to “repopulate” Amboseli with zebras after the drought, by trucking them in from Naivasha, came to nothing. But the zebras, like wildebeests, clung on to life and are now surging back. Nature is more powerful than we credit.

Thanks Keith – I think the only animals to gain from the assisted ‘repopulation’ attempts were the hyenas! We heard recently from Sue and Jamie Roberts that a small number of hippo were seen in the lower reaches of Mzima, so hopefully they will slowly make their way up to the top pools.

Reblogged this on Sherlockian's Blog.