Alan Root was a filmmaker’s filmmaker – he combined a sharp intellect and a need for adrenaline-fuelled adventure, with a knowledge of African natural history that was unparalleled. He was passionate and humorous – a quick-witted story-teller who revelled in his art. He loved to be the centre of attention and he didn’t suffer fools, but there was a sensitivity behind the public face, that expressed itself in his filmmaking.

In a world where natural history films have become increasingly formulaic, made by big teams with big budgets, backed by an army of researchers, scientific advisers, and camera-people, Alan was the original auteur. He filmed and wrote and ‘lived’ the films that he made together with Joan, his first wife. Their films were individual and visually arresting, but above all, they were stories. They combined natural history integrity with irreverence, and humour. They conveyed a knowledge of natural history and wildlife behaviour that few could equal.

Alan invited us out to East Africa to film a series with him for ‘Survival’ in 1986. For a year we tried to turn him down – we already had a career filming underwater. But he was as persistent as he was charismatic, “Come on guys – you’ve got to evolve; crawl out onto land. Come up into the sun. It’s happened before…”

In the end, we couldn’t refuse. For us, Alan and Joan’s films were peerless – he told stories like nobody else, and he had complete creative control of his films. We had a lot to learn.

Our three years in East Africa turned to thirty. Alan started as the director who flew down to Serengeti every few months to deliver and critique our rushes – but soon became friend, mentor, soulmate…

He presided at our wedding in the bush; he cut the roof off his range-rover and covered it in bougainvillea to ‘give away’ Vicky; he was executive producer on our films; he was ‘Babu’ to our boys.

In the 80’s Alan was at the peak of his career. His films were always ‘events’ – to be looked forward to for years, and then cherished and enjoyed for decades afterwards.

He was always ahead of his time – the technical achievements of a film like ‘Mysterious Castles of Clay’ were matched only by the likes of Oxford Scientific Films – but Alan didn’t want to film extreme macro in a studio. He wanted to achieve it in the field, even if it meant months of excavating termite mound after termite mound, to find the royal chamber, and then introduce lights, slider, and turntable.

If he wanted his audience to experience the termites’ point of view of what it was like for the colony to be raided by an aardvark – that meant Joan putting years into raising an orphaned aardvark to accomplish it.

Alan never did ‘average’ – he approached everything as if it was his last day on earth. Then he pushed the boundaries so that, in many cases, it almost became that. He lost so many body parts to encounters with wildlife that the New Yorker sent George Plimpton to write an article about it. Alan gave the interview, lying on his back beside the fire at our camp in Mzima. He’d just flown for five hours after injuring himself in a motorbike accident in the forest in Zaire, and his lip was in tatters after a ‘tame’ marsh mongoose had fastened on and decided it was edible.

Alan was a fine bush pilot, with an eagle’s instinct for stalls, side-slips and gliding. He never finished flying school – but bought an aircraft and when he thought he knew enough, simply flew off one day and didn’t return. He liked nothing better than to fly from Naivasha down to Serengeti, 10m off the ground, reeling off the names of the birds he spotted on the way.

Not content to simply ‘buzz’ a lodge to declare his arrival, he would fly straight at it, and at the last moment, as the guests dived for cover, pull up and bounce the wheels of his 1954 Cessna 180 off the thatch roof.

A helicopter followed, but Alan was more eagle than hummingbird. He thought nothing of learning to fly rotary aircraft in his 60’s, but it meant trying to drop the habits of a lifetime. He crashed the first, then the second, and then, when he could no longer get insurance, bought another – only more powerful and much more expensive. His explanation: “It was the only way to make me concentrate…”

As a teenager, he made his first film about lily-trotters on Lake Naivasha. He was the first to film the adults gathering their young beneath their wings to carry them as they strode across the lilies. But he wasn’t content with that – he wanted to know what would happen if the lily pads were spaced further apart, and the birds felt the need to add a flap to their jump – would they drop their babies in the water? It was the birth of an approach that would recur in later films – first-class natural history detective work and then, ‘what if…?’

When Alan was 21, his best friend, Michael Grzimek, a cameraman, was killed, when the Dornier he was piloting, hit a vulture in the Sanjan gorge in Serengeti’s Gol mountains. The collision trapped the control cables in the leading edge of the wing and caused the plane to crash. Alan went on to finish the film Michael was shooting. “Serengeti Shall Not Die” won an Oscar and, as Alan declared, “It was all downhill after that”.

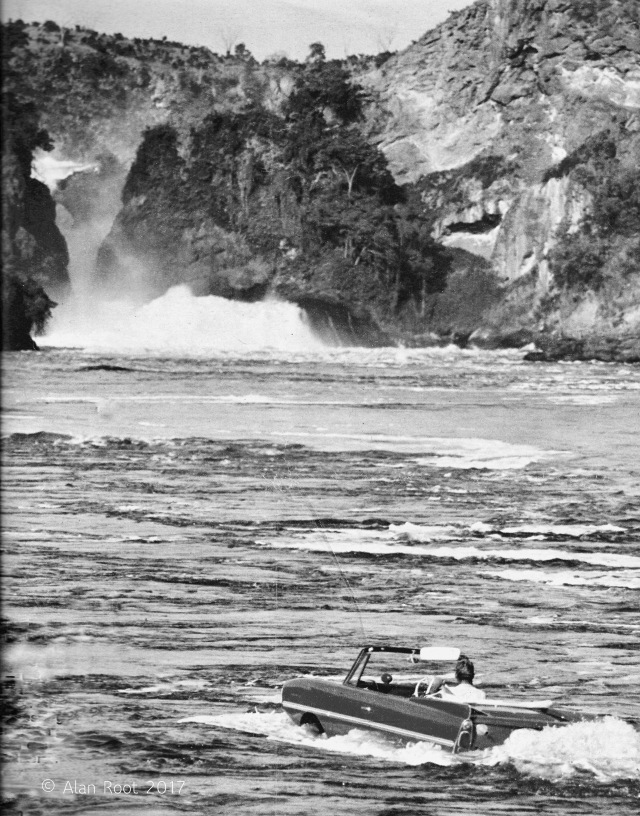

His break into television came with one of two films he made for the BBC, ‘Mzima – Portrait of a Spring’. Alan convinced the BBC that he’d be able to get underwater to film hippos and crocodiles. The BBC agreed to fund half the film’s budget and wanted to Alan to shoot in black and white. Alan and Joan wanted to film in colour and agreed to cover the field costs, in return for the rights for the rest of the world. Despite Alan getting severely mauled when they got caught up in a fight between two male hippos, the film got finished and became an instant success. They subsequently sold it in the US to CBS and they never looked back.

Fifty years ago, the BBC didn’t share Alan’s vision for selling wildlife films worldwide. They didn’t think there would be a market; but an independent ‘start-up’ did. Aubrey Buxton had just established ‘Survival’ at Anglia TV. It was a natural fit and the start of a relationship that would last almost forty years.

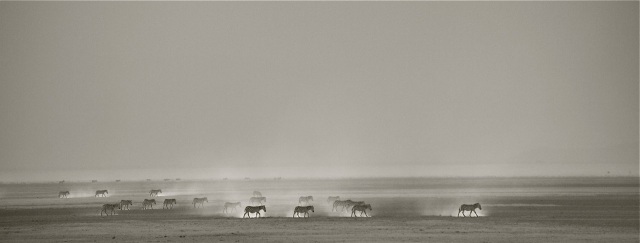

The films that followed, ‘Year of the Wildebeest’, ‘Mysterious Castles of Clay’ and ‘Two in the Bush’, became wildlife classics.

Always resourceful, Alan used every trick he knew to film new and exciting behaviour and tell exquisite wildlife stories. He pioneered the use of remote cameras and hot-air balloons for wildlife filmmaking.

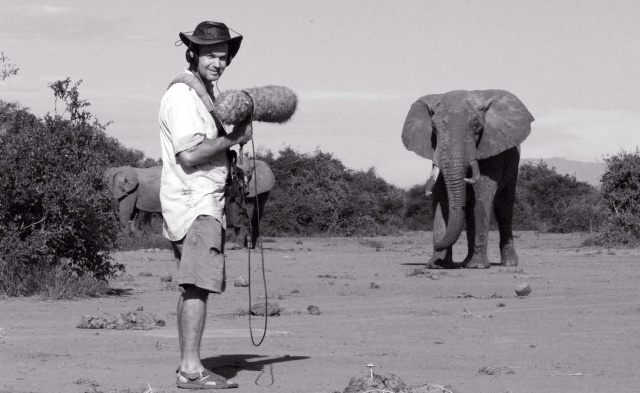

He was an excellent mimic – he’d attract birds to film them, by imitating their calls. If he needed additional wildlife sounds in track-laying, then his repertoire of baboon alarm calls, elephant farts and wildebeest contact calls was extraordinary.

He loved to catch snakes – cobras, mambas, boomslangs … the more venomous, the better. He couldn’t walk past a puff-adder without picking it up, but he was vocal about presenters that he felt molested or exploited wildlife.

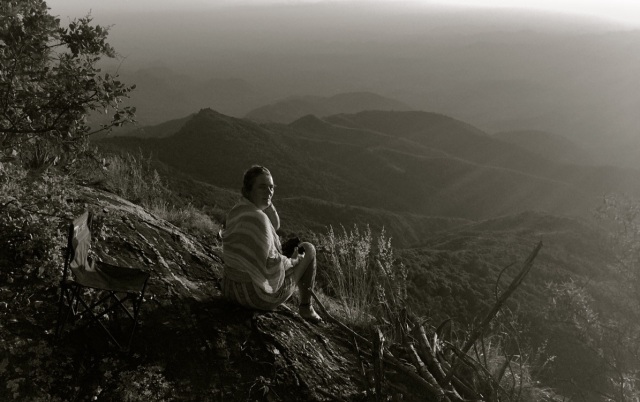

Alan planned to celebrate his 80th year in a way that was typically audacious and would take him back to his spiritual home, the Serengeti. It would be a film about following the wildebeest migration – in the company of lions and hyenas.

He planned to follow the migration alone and on foot.

It would be the antidote to the over-hyped jeopardy of wildlife ‘reality tv’, of which he was so dismissive. It would be forty years after he’d made ‘Year of the Wildebeest’; sixty years since ‘Serengeti Shall not Die’ – he had plenty to celebrate.

Unarmed, except for his wits and a bottle of sunscreen, he planned to walk with the wildebeest from the short-grass plains in the south of Serengeti, up into Kenya’s Maasai Mara. He knew it might take weeks, but he was prepared. He’d designed body mounts for cameras, and had a drone that would follow him. He knew that National Parks would never give him permission, so he planned, as so often before, to go in ‘under the radar’. A Serengeti safari with his wife Fran and teenage sons, Myles and Rory would give him the cover he needed to bury caches of food, water and batteries along the route. He’d have no contact with anyone on his ‘amble through the Pleistocene’, but he’d carry a gps tracker, so once Myles and Rory knew he’d visited a ‘drop’, they’d go in after him to remove any trace, and pick up expired batteries and memory cards.

It was pure Alan Root – the maverick filmmaker, making a statement, as only he knew how. Sadly he didn’t live to make happen.

To spend time with Alan’s films, is to enter a world where the wild animals are the stars, and the story is the way to engage with them and bring them to an audience. Alan and Joan’s films had a global audience of hundreds of millions. He had boxes of awards – an Oscar, Emmys, Peabodys… He was honoured with international lifetime achievement awards and, more recently, an OBE – he declared it an acronym for “Other Buggers’ Efforts”. Nothing can have been further from the truth.

R.I.P Alan – we miss you.